COY CATS TELL TALL TALEs / the years like birds fly

PHOTO BOOK (2018)

Do-si-do self-published artist book with tucked-in essay booklet

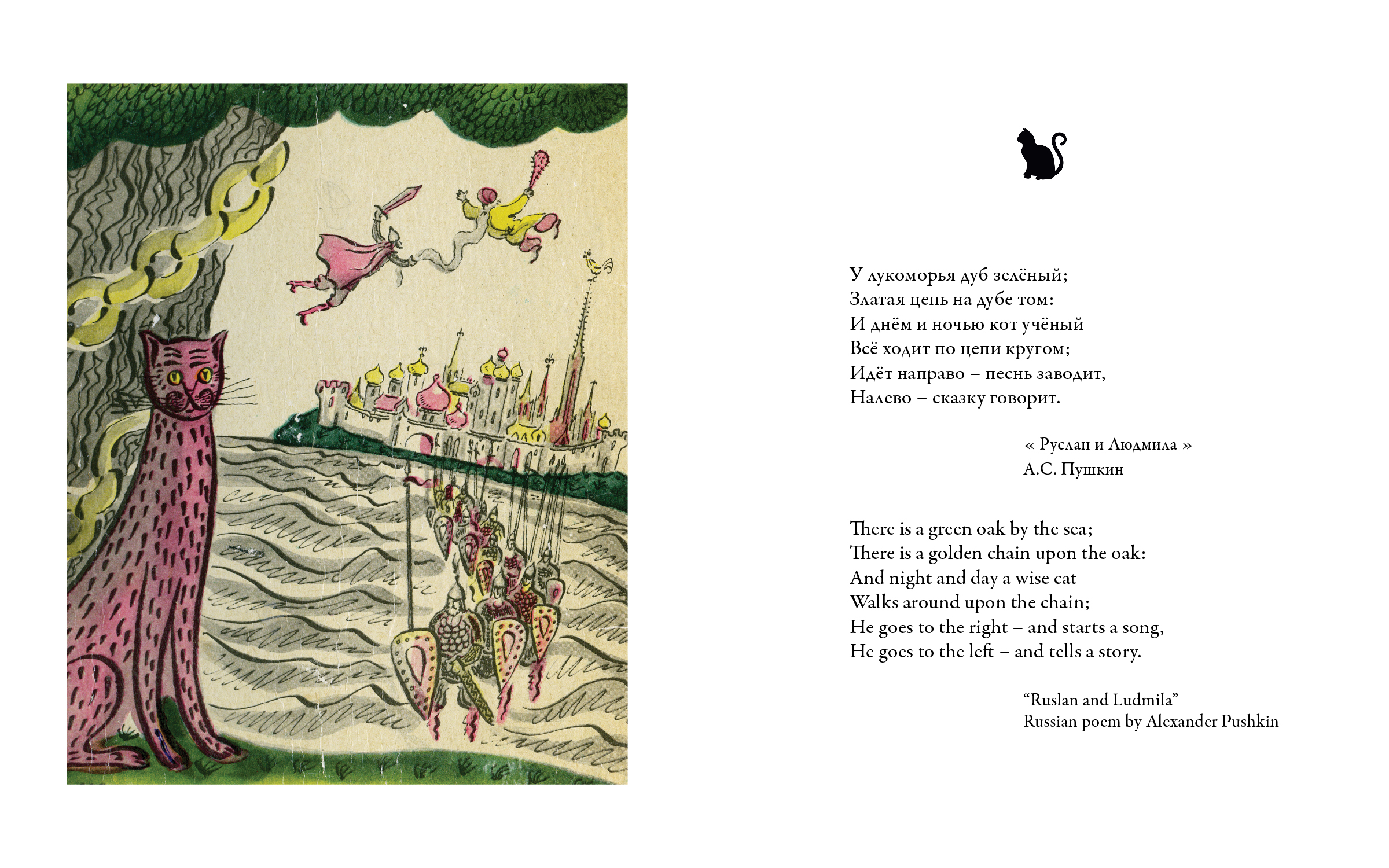

Illustrations from the artist’s Russian children’s book collection

THE MYTH OF KOSTROMA

Essay by Rita Kovtun

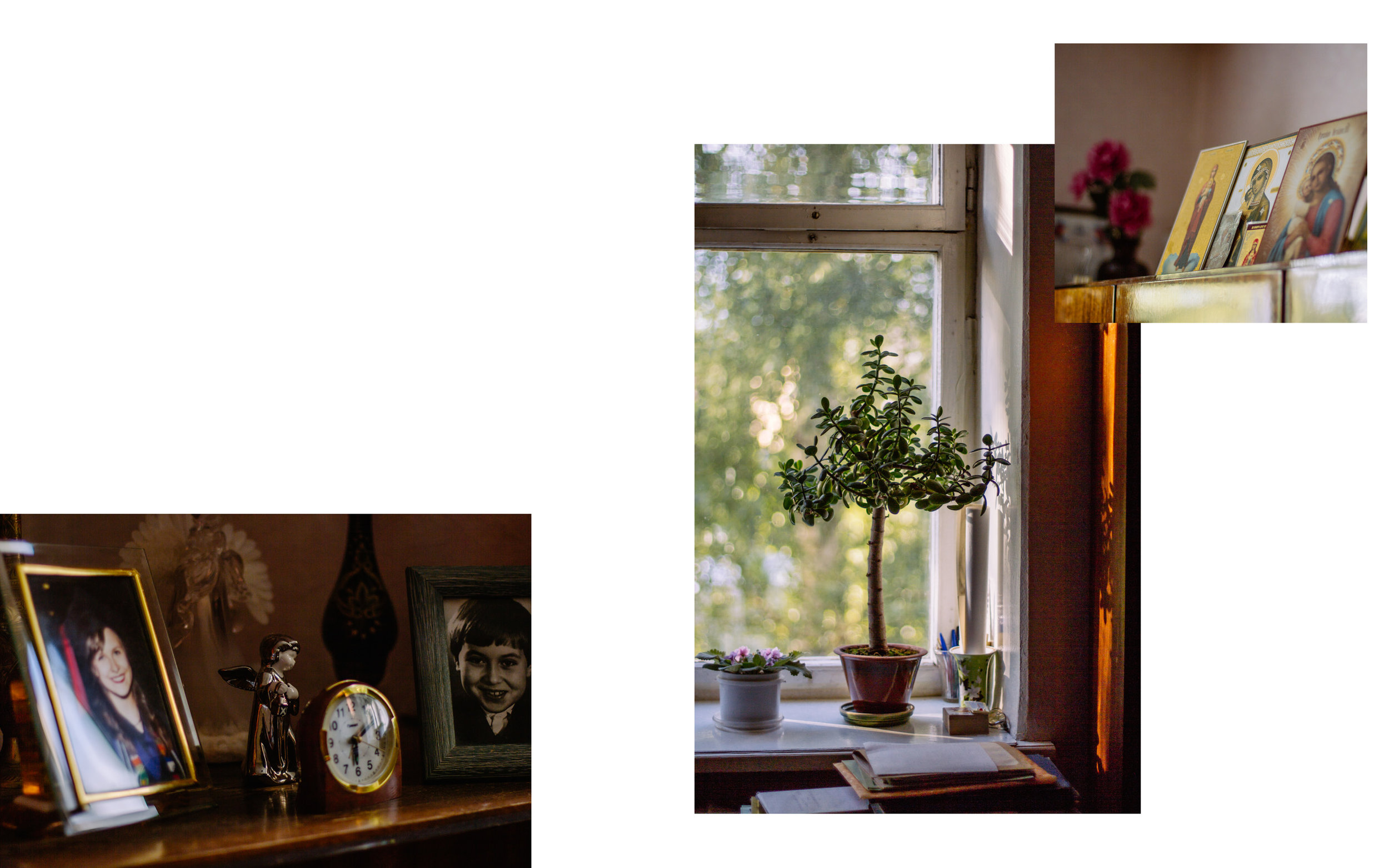

No matter how long I spend away from my grandparents’ apartment, I feel that I can always recall it in vivid detail. The rush of warmth that is the soft atmosphere, dim light, and Babulya’s joyful smile upon stepping inside from the solemn, concrete walls of the building’s stairway. The gentle shaking of china in its display case upon walking into the living room where an omnipresent old rug in tones of cream and maroon hangs on the wall. The white lace curtains gently dancing in a breeze from the kitchen window. The Virgin Mary ever watching from Babulya’s many icons. The shrill, long creak of the wooden wardrobe’s door. The quiet play of light through the trees, coming in through the bedroom window in the late afternoon.

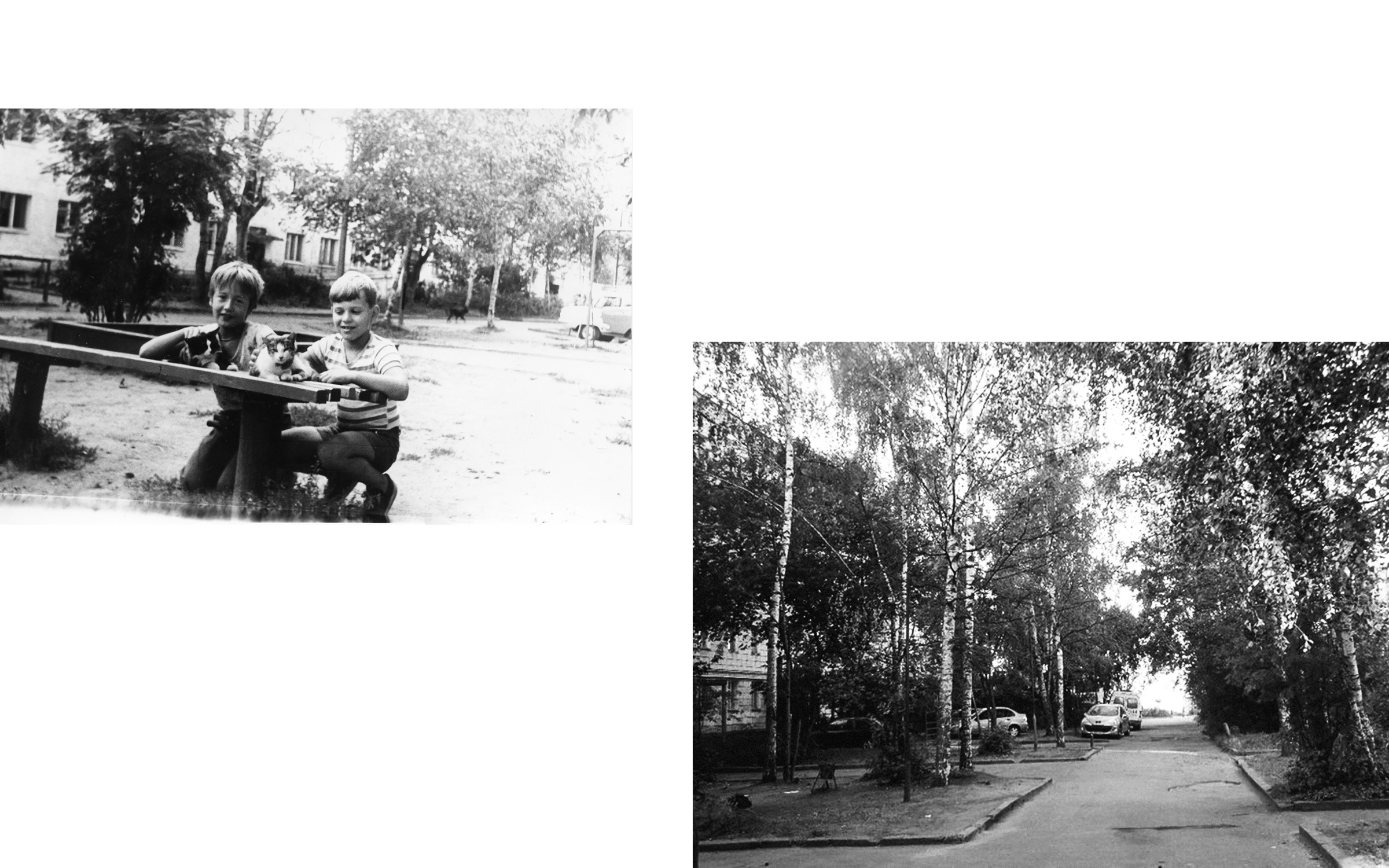

Growing up, this had been my second home—or perhaps, my real home. Before the age of 11, my family moved every few years. Russia to Texas, Texas to California, California to an apartment in Minnesota, to our first house, and then to our second. My family kept ownership of the small apartment in my hometown of Odintsovo, a suburb of Moscow, which we rented out while we lived in America. That apartment never felt like home—it was just a place to pass through. The one constant through it all had been a month or two every other summer spent at Babulya and Deda’s apartment and dacha (a summer home and garden, similar to a cabin) in Kostroma, a historic city roughly six hours northeast of Moscow by train.

I had friends in Kostroma—a crew that I could pick back up with whenever I returned. During the time in between, we wrote letters. In Kostroma, at the end of July, they’d come to my birthday parties. Sometimes I’d go to a summer camp run by one of Babulya’s friends and swim in the Volga with her granddaughter Katya. I spent my days listening to stories like The Adventures of Grasshopper Kuzya and The Bremen Town Musicians on my grandparents’ record player.

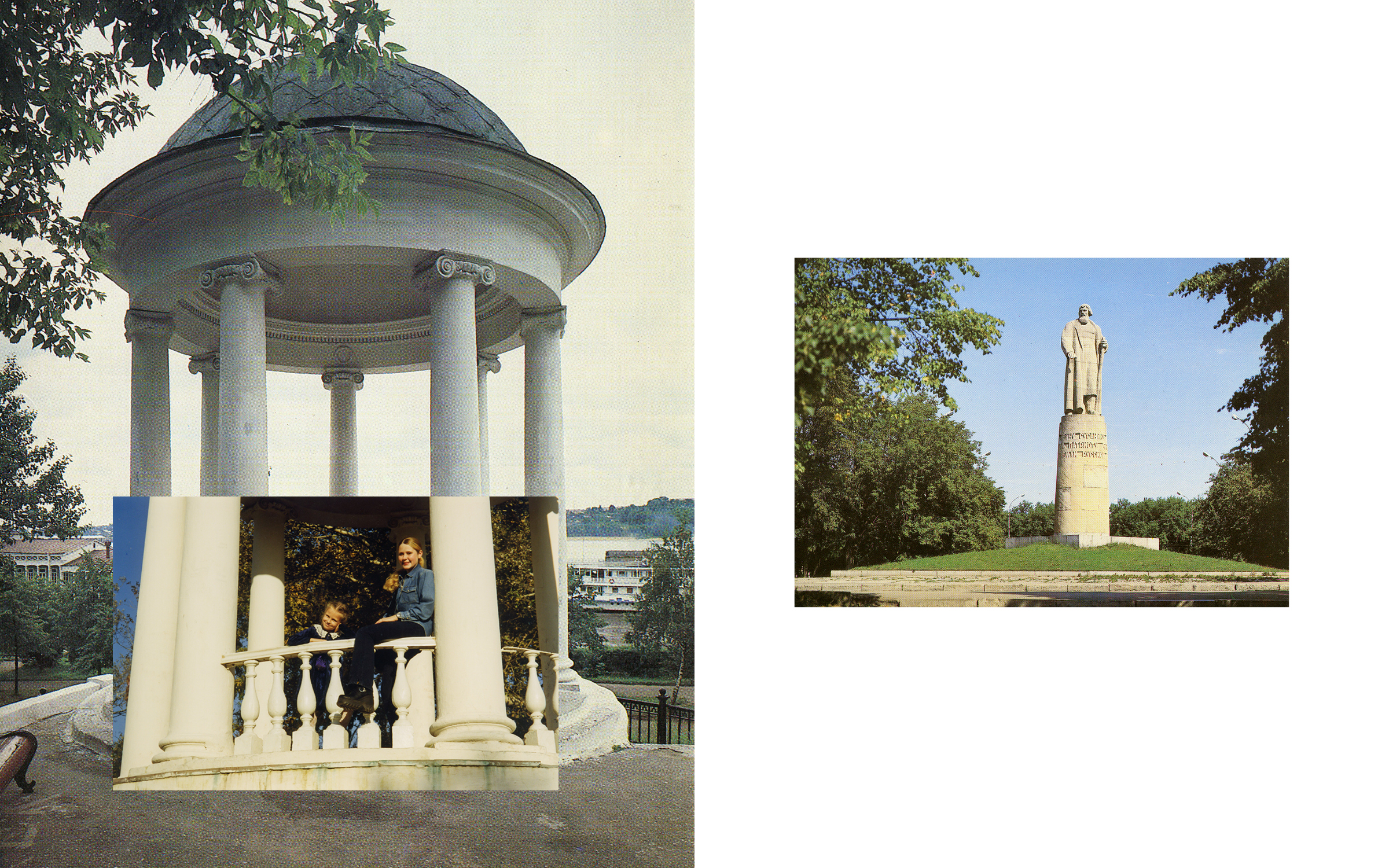

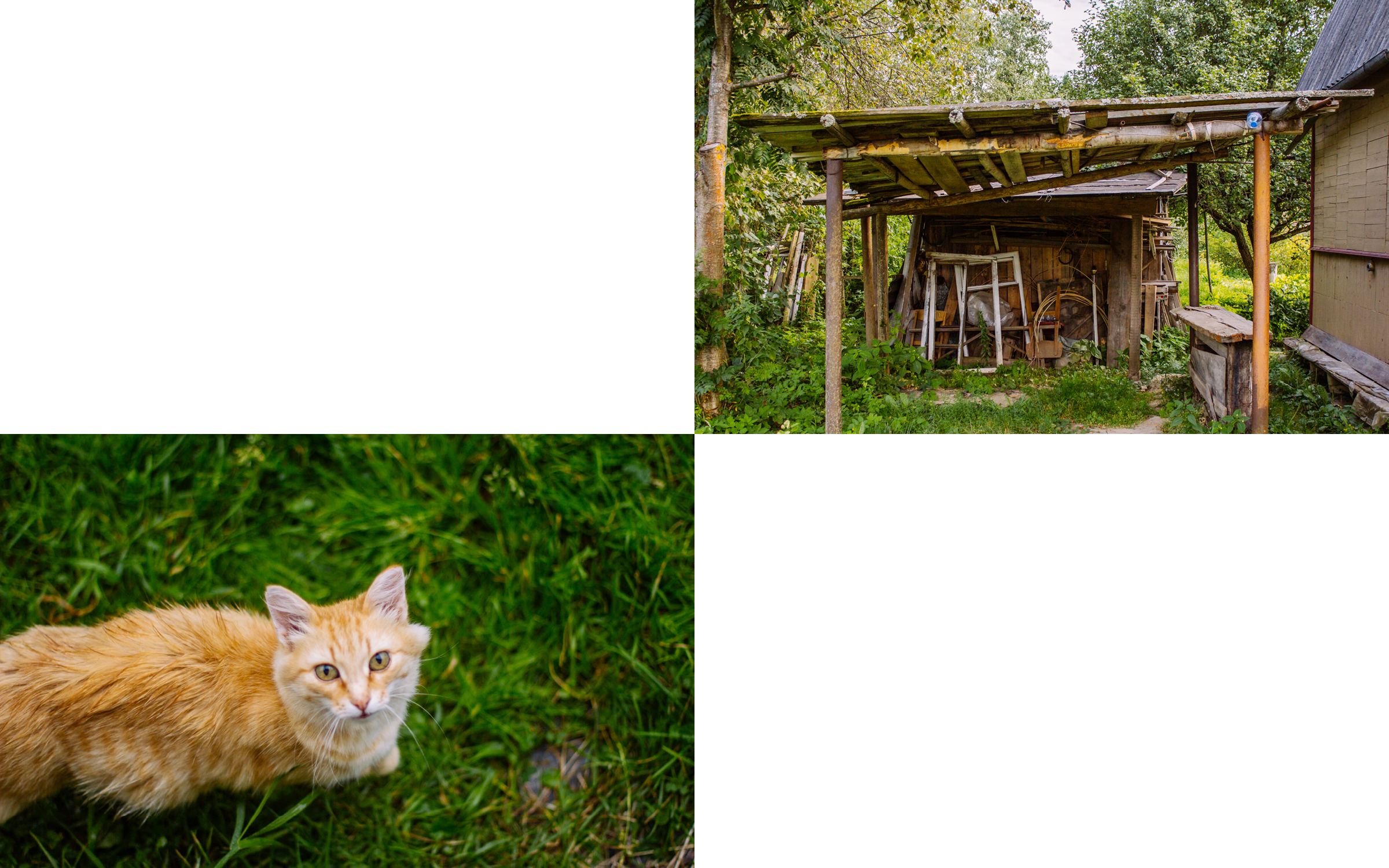

And at the dacha, located twenty or so minutes outside the city of Kostroma, there was always an endless amount of things to do: swimming in the river, helping pick currant berries that Babulya made into jam and wine, playing with the neighbor kids, catching holographic green beetles and lizards, getting family and friends together to eat and drink and sing songs, staying up late playing cards, and then sleeping in the little room where an exotic bird cross-stitched by Babulya watched over me all night. The dacha was my childhood haven of love, laughter, and light.

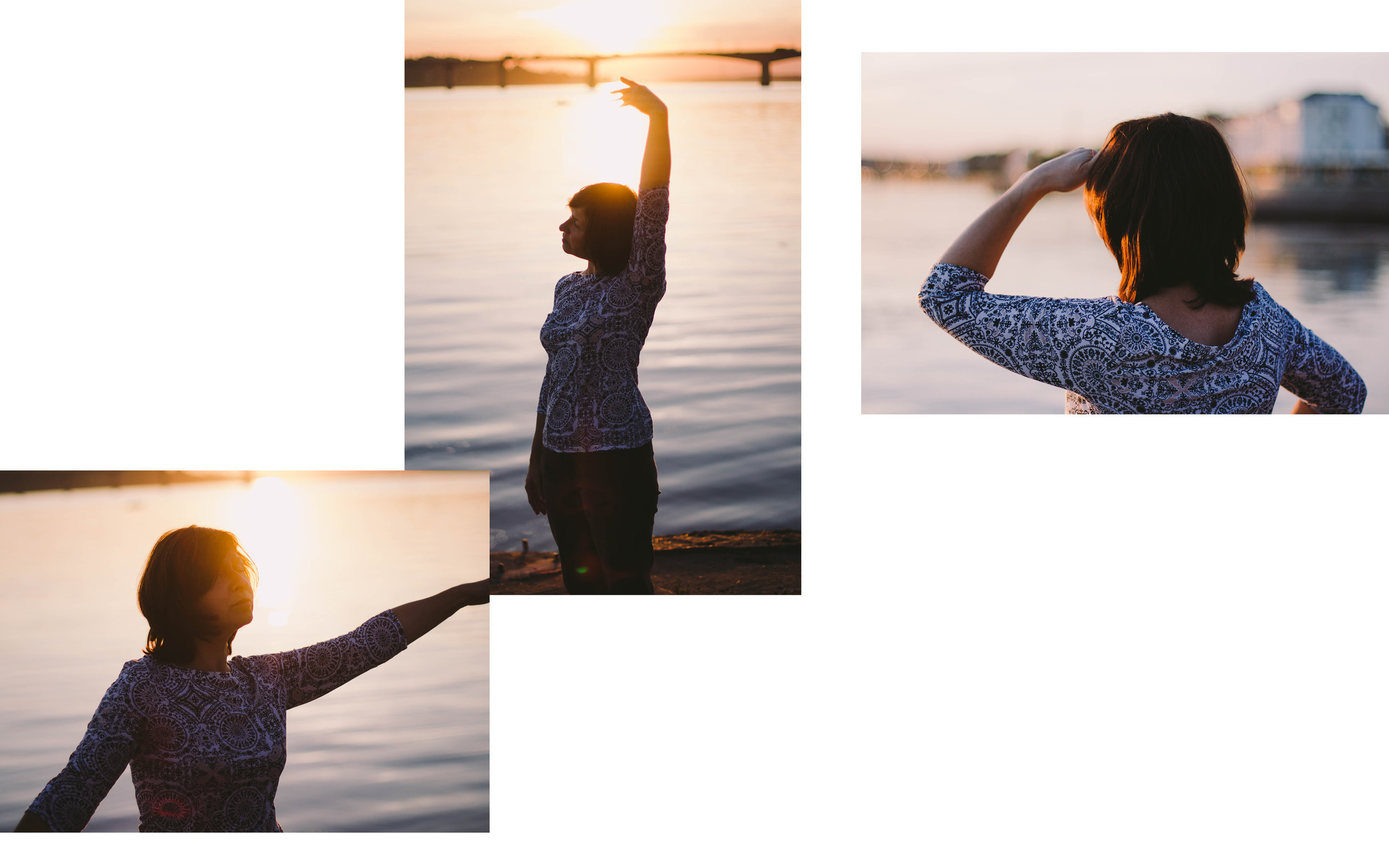

It felt like the gaps between me and my grandparents only widened as I grew up—because of our ages, our cultures, our religions, and our distance. We talked so rarely unless we were physically together that when Deda passed in 2014 and Babulya in 2016, it almost felt like nothing had changed. Their death is surreal because it will only be real, only felt, when I go back to Russia and enter the

spaces that hold our shared memories.

I’ve come to realize that the life of a person can live on as long as memory can carry it forward. As long as those memories are alive, the person is alive, if only for the caretakers of those memories. I worry about how I will carry and transfer on a legacy that is only a fragment of who I am. But that is the story of all immigrants—an assimilation over generations, with more memories, stories, culture, tradition, and history lost every time until it only exists in legend, twisting and fading into myth.

The death of my grandparents isn’t just the ending of two lives. It’s the dying off of a generation. It’s the orphanage of my mother. It’s a closed door on a part of my childhood that lived on into my adulthood—one I never fully fathomed ending. It’s the burial of stories and secrets that died along with their keepers. I bear the weight of telling the stories of my grandparents, though sometimes they are ones I don’t fully know or remember without aid from my parents.

A big part of my Russian upbringing was the childhood stories and fairy tales—in books, records, films, and television programs. I have returned to these stories over my adult life as they anchor me to a time when things were simpler. They are fantastical, mythical, and beautiful. They are tied up with the myth of my childhood, the myth of my grandparents, and the myth of Kostroma.